The Palazzo Venezia on the Piazza di San Marco

by Joanna Mundy

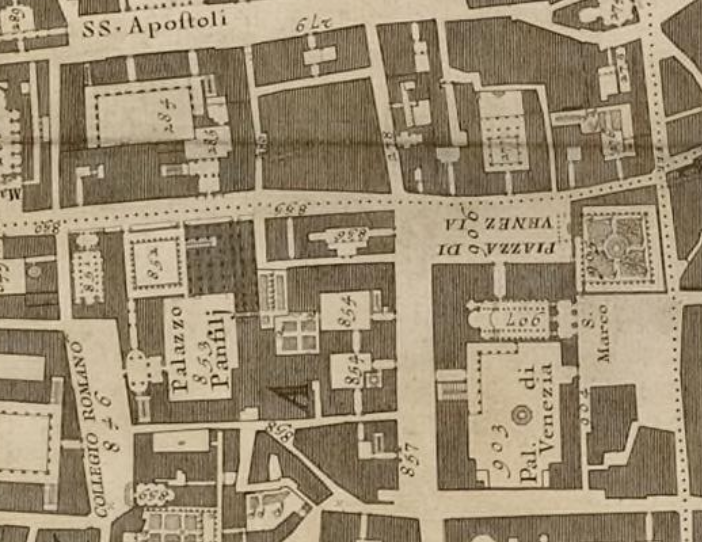

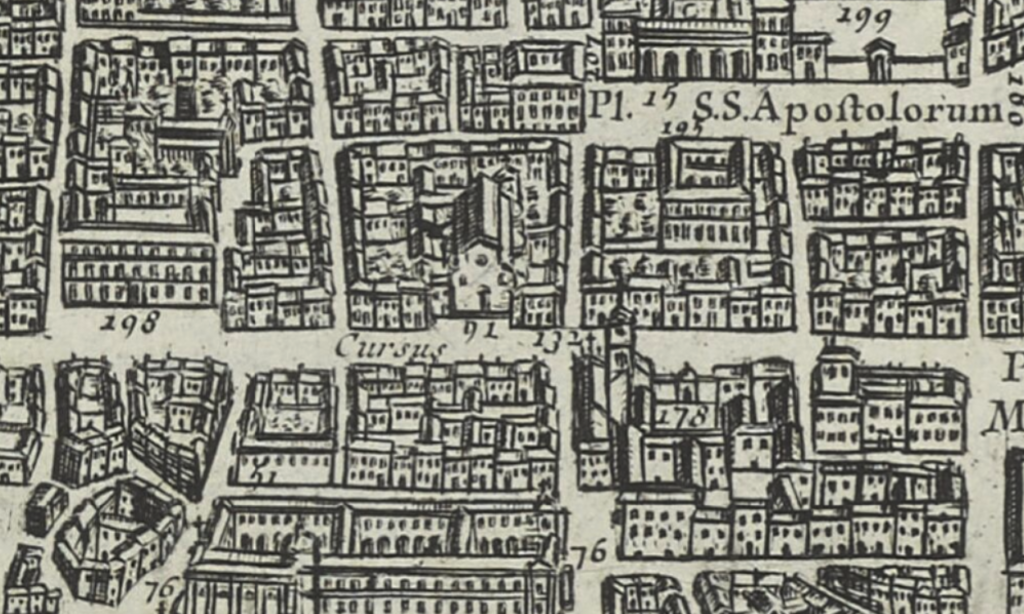

The piazza at the southern end of the via del Corso is positioned at a critical point. This piazza caps movement down the via del Corso and offers a view of buildings climbing the Capitoline hill or Campidoglio. The piazza is identified by Giovanni Battista Falda on his 1676 map Nuova pianta et alzata della citta’ di Roma as the Piazza di San Marco (fig. 1) and by Giambattista Nolli in his 1748 Nuova Pianta di Roma as Piazza Venezia (fig. 2).

The piazza underwent multiple changes over time. Originally referenced in documents as the Platea Nova, and for a time labelled the Piazza della Conca di San Marco for a large stone Roman tub placed there by Paul II, it was later called the Piazza di San Marco for the nearby basilica, and has come to be called Piazza Venezia for the adjacent Palazzo Venezia, given to the Republic of Venice in 1564.[1] Falda refers to the palazzo as the Palazzo di San Marco della Republica Veneta or Palazzo di San Marco in his prints and the Palazzo Ambasciadore di Venetia in his 1676 map, though we will use the more familiar Palazzo Venezia here.

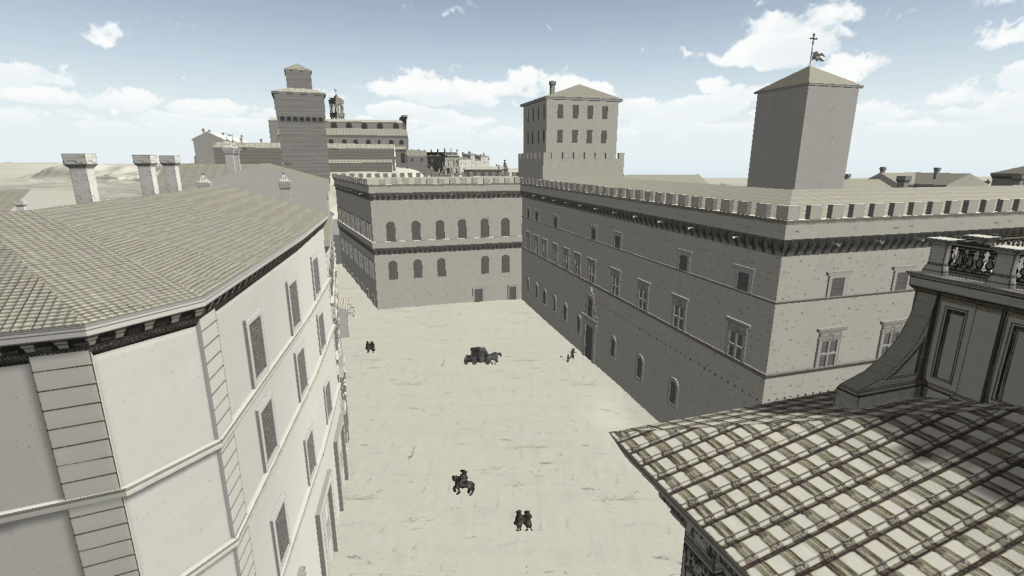

In 1676 the Piazza di San Marco was much smaller than the modern Piazza Venezia. It was expanded in 1909-1910 for the construction of the national monument built to honor Vittorio Emanuele II, which rose between 1911 and 1913. The expanded piazza was intended to provide an open view of the monument from the via del Corso.[2] Multiple interventions in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries took place at the palazzo, which resulted in a regularization of the windows on the east side. In the years 1908-1911 the Palazzetto, or small palace, originally located to the southeast of the palazzo, was destroyed to make way for the expanded Piazza Venezia and the national monument to Vittorio Emanuele II. A new version of the Palazzetto was reconstructed between 1911 and 1913 under architects Camillo Pistrucci, Ludovico Baumann and Jacopo Oblatte in a different position adjacent to the palazzo, and required some adjustments to the previous plan in order to fit the new space. The interior portico, however, was dismantled and reconstructed precisely, but for a single arch on each side removed to fit the new smaller dimensions.[3] Our reconstruction of the piazza and adjacent buildings ca. 1676, based on the map and prints of Falda, allows viewers to immerse themselves in the earlier urban space, still closed in by palazzi, now altered or lost, and to gain a sense of the seventeenth-century articulation of the piazza, streets, and buildings in this important part of the early modern city.

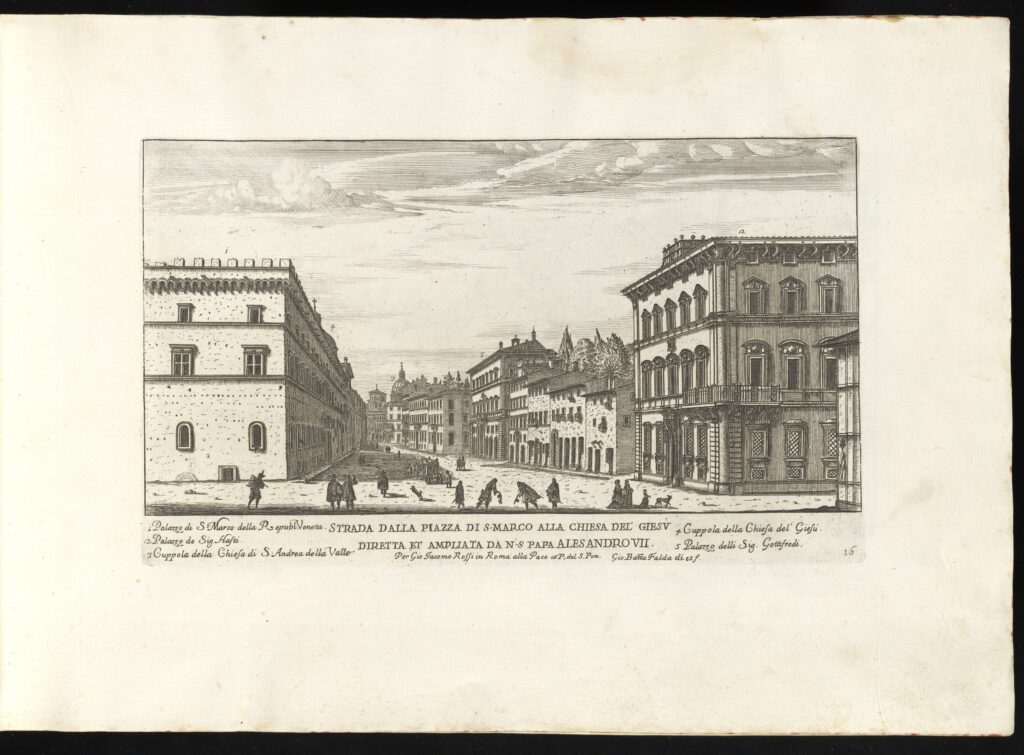

In order to begin the reconstruction of this part of the city in 1676, we used the map and prints showing this urban space created by Giovanni Battista Falda as our key sources. The only image that Falda presents of the full façade of the Palazzo Venezia is found in his first published print Disegno delle Fabriche Prospettive e Piazze Fatte Novamente in Roma D’Ordine della S. di N. S. Papa Alexandro VII from 1663 (fig. 3). While this print only includes the piazza as a small detail, identified as the piazza e stradone a S. Marco, the explicit view of the façade made it a key source for our reconstruction.

-

Figure 4: G.B. Falda, Strada dalla Piazza di S. Marco alla Chiesa del’ Giesu Diretta et Ampliata da N. S. Papa Alesandro VII, 1665. -

Figure 5: G.B. Falda, Piazza di San Marco, 1643-1678.

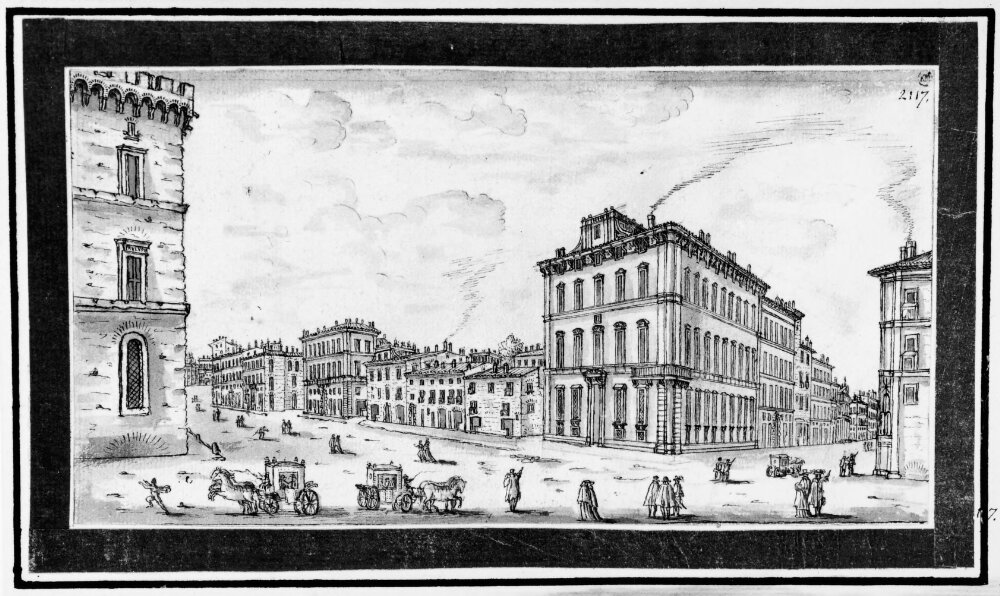

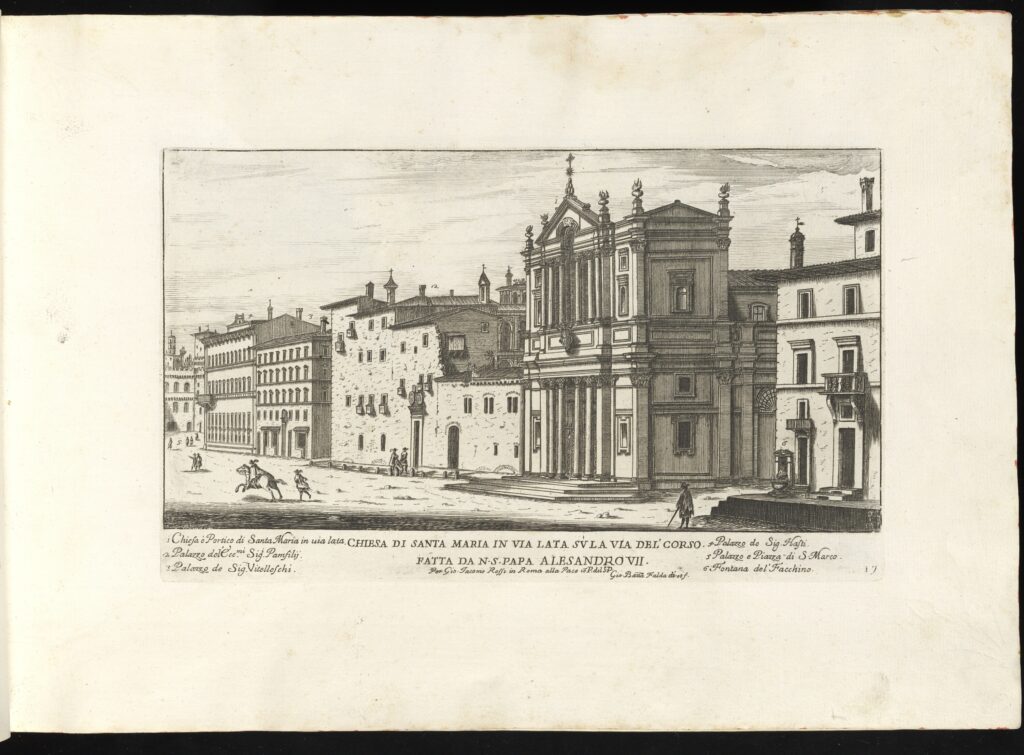

The Palazzo Venezia is also visible in the background or at the edge of some of Falda’s prints from Il nvovo teatro delle fabriche, et edificii, in prospettiva di Roma moderna, (vol. 1, print 16 and 17, and vol. 3, print 7 and 20). Among the Il nuovo teatro prints, Strada dalla Piazza di S. Marco alla Chiesa del’ Giesu Diretta et Ampliata da N. S. Papa Alesandro VII, vol. 1, print 16, shows the largest portion of the building. It shows the final two bays on the east façade facing the Piazza S. Marco, and the entire north façade, rendered at an extreme angle, facing the modern Via del Plebiscito (fig. 4). An earlier pen and ink drawing of this view by Falda can be found in the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm (fig.5). In the print Chiesa di Santa Maria in Via Lata Su’ La Via Del’ Corso Fatta da N.S.Papa Alesandro VII, vol. 1, print 17, part of the north facade of the Palazzetto Venezia on the Piazza S. Marco is visible in the distance (fig. 6). This print provided a bit more detail of this northern facing façade of the Palazzetto on the Piazza S. Marco, which is rendered at an extreme angle and in shadow in the 1663 detail from Disegno delle Fabriche Prospettive e Piazze Fatte Novamente (fig. 3). Chiesa di Santa Maria in Via Lata… also provides a clear view of the church of Santa Maria in via Lata, another key building in this neighborhood (see below). Further sources were found in vol. 3, where in print 7, Chiesa Dedicata alla Madonna de’ Loreto de Fornari nella Regione de Monti, the southern end of the Palazzetto Venezia is visible, providing more information, including the number of rows of windows (fig. 7).

-

Figure 6: G.B. Falda, Chiesa di Santa Maria in Via Lata Su’ La Via Del’ Corso Fatta da N.S.Papa Alesandro VII, 1665. -

Figure 7: G.B. Falda, Chiesa Dedicata alla Madonna de’ Loreto de Fornari nella Regione de Monti, 1669.

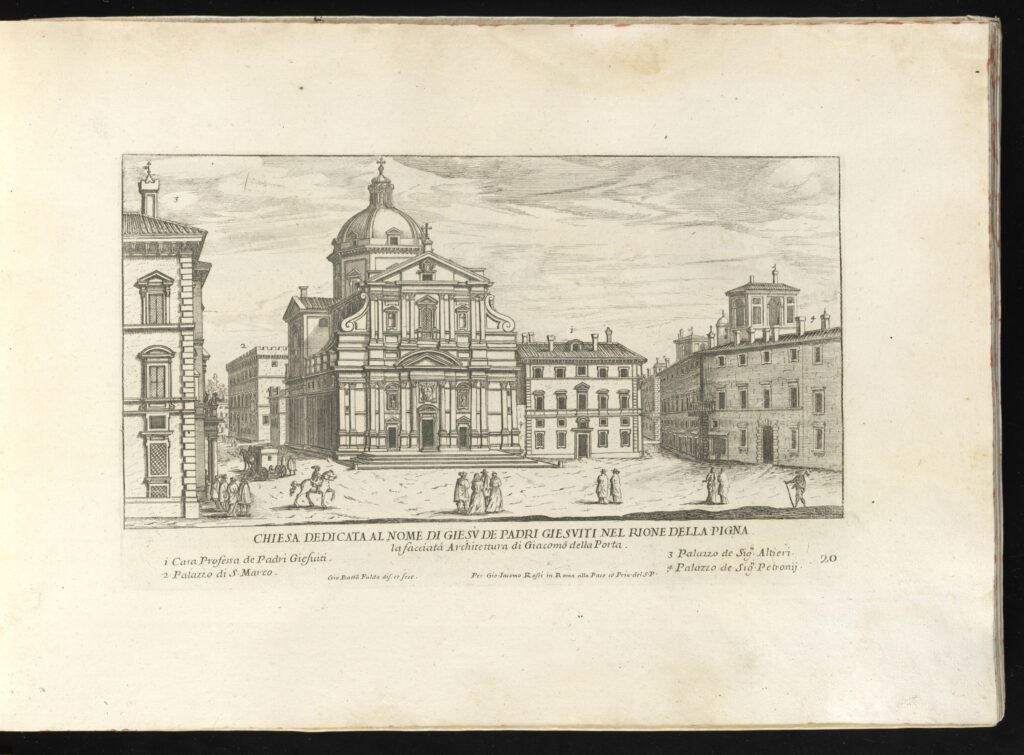

Finally, in the print Chiesa Dedicata al Nome di Giesu’ de Padri Giesuiti nel Rione della Pigna, vol. 3, print 20, the north façade of the Palazzo Venezia along the modern Via del Plebiscito (fig. 8) is shown from the direction of the Palazzo Altieri. This view allowed for comparison to the façade’s appearance in vol. 1 print 16 (fig. 4). Together, these prints made up our primary sources for the reconstruction of the Palazzo Venezia and the Piazza di San Marco.

Working from these sources, our first challenge was to determine the details of the façade of the Palazzo Venezia. This building, despite its prominence in the city of Rome, did not undergo significant alteration during the seventeenth century. As a result, Falda does not focus on its representation and it is not among the palaces included in the second volume of the Palazzi Di Roma De Piu Celebri Architetti: Nuovi Disegni Dell’ Architetture, E Piante De Palazzi Di Roma De Piu Celebri Architetti.[4] We compared details from the multiple angled views he does provide to determine the layout of the façade, including the correct placement of doors and windows.

In the most complete view of the east façade, the detail from Disegno delle Fabriche… (fig. 3), Falda depicts twelve windows, six each on two levels, to the south of the main door, and eight windows, four each on two levels, to the north of the door. The four windows to the north of the door on the bottom row have a slightly different shape, with an arched top, from the lower windows to the south. A further row of openings on the third level includes seven windows over the full length of the façade, irregularly placed. The central door has a window above it, and one of the seven small windows from the third row above that. The central door is larger and more decorative than the windows and has columns on either side. The print also shows three small brick relieving arches along the base and one low rectangular-shaped support at the ground level. The print does not provide much detail as to the window surrounds, details of the door, and other points of the structure. Strada dalla Piazza di S. Marco (fig. 4) supports the arrangement of the façade as seen in the Disegno delle Fabriche…, showing the final two bays of the façade facing the Piazza di San Marco, and the entire façade facing the modern Via del Plebiscito at an extreme angle. The two bays in this much more detailed print closely match those from the simpler 1663 print. The only major difference is the addition of another small rectangular opening at ground level toward the northern end of the façade.

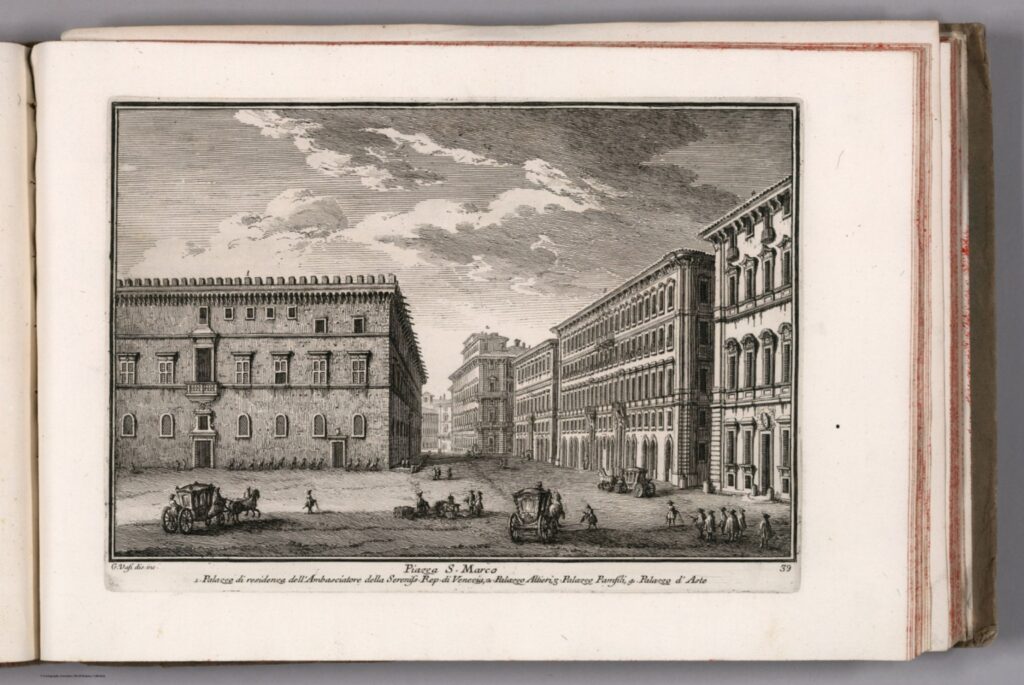

For further confirmation, particularly of the details of the east-facing façade toward the Piazza di San Marco, we compared the two Falda prints discussed above with Vasi’s Piazza S. Marco (fig. 9).[5] Vasi shows a similar pattern of windows on the northern side of the central door. The central door itself looks mostly unchanged, although the window immediately above it is shown as more decorative. The windows in the lower row to the south of the central door look as if they had been regularized at some point between the mid to late 1600s and 1752 in order to match those to the north. Likewise, there have been changes to the top row of small irregular windows. The other major difference visible in the Vasi print is the final opening on the northern end below the bottom row of windows. In the Vasi print the small rectangular opening at ground level, seen in Falda’s Strada dalla Piazza di S. Marco… (fig. 4), has been raised and now has the height of a full door. While the Vasi print includes many changes from the early eighteenth century, it provides support for Falda’s depiction of the façade. The print was also helpful in providing more detail for the appearance of the central door, which seems to have remained unchanged between Falda’s time and Vasi’s.

Having considered all of the evidence outlined above, we chose to follow the pattern of windows as shown in Disegno delle Fabriche… (fig. 3). This early Falda print provides the most complete depiction of the east facade and other Falda views support its representation. For the detail of the façade, however, we also utilized the building as depicted by Falda in Strada dalla Piazza di S. Marco… (fig. 4), as it is a larger and later print.

The Piazza di San Marco and Vicinity

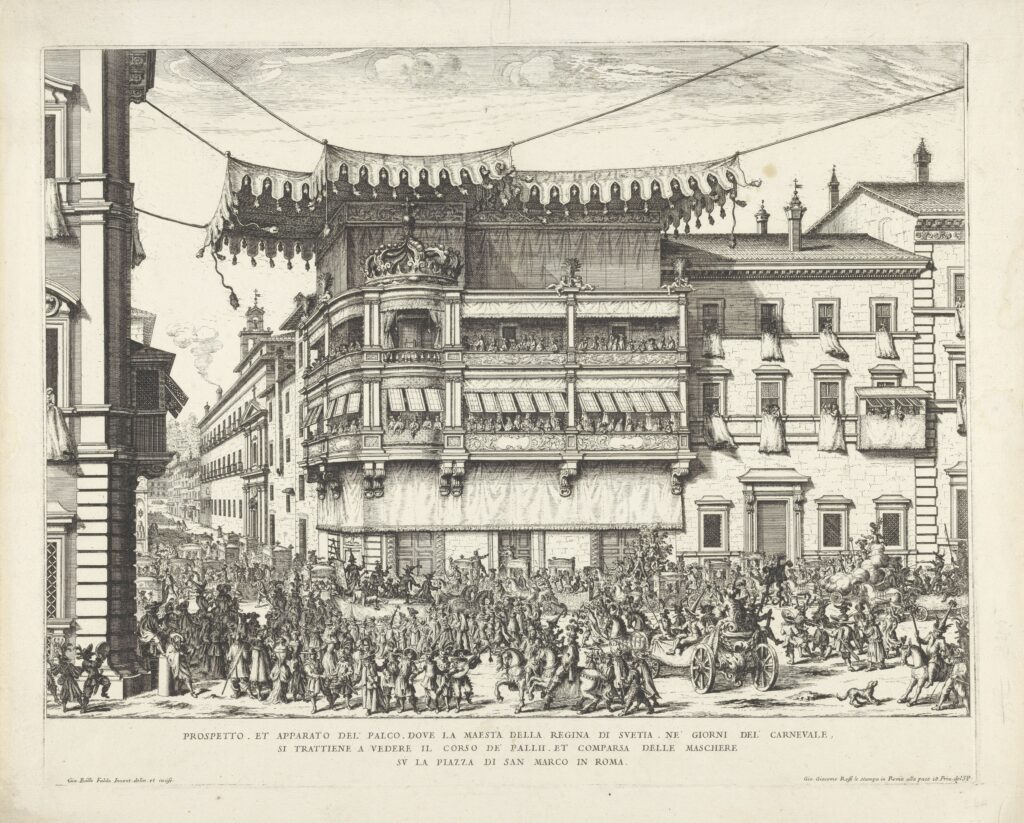

The Palazzo Venezia, the Piazza di San Marco, surrounding streets, and key palazzi make up this quarter of Baroque Rome where events, such as Carnival and processions, including the arrival of Queen Christina of Sweden, took place. Additional sources provided key details that helped us to reconstruct the palazzi in the area of the Piazza di San Marco. Of particular prominence in the area are the Palazzo D’Aste, on the corner of the Piazza di San Marco and the via del Corso, the Chiesa di Santa Maria in via Lata and the Chiesa di San Marcello al Corso, a couple of blocks up the via del Corso, the palazzi opposite the Piazza di San Marco from the Palazzo Venezia, and the Palazzo Gottifredi, down the modern via del Plebiscito in the direction of the Palazzo Altieri.

An additional print created by Falda provides further cultural context and detail on the Piazza di San Marco. This print depicts a temporary balcony, marked by the Swedish crown, made for Queen Christina so that she could watch, undisturbed, the celebration of Roman Carnival (fig. 10). The first detailed description of this balcony dates from an account written in 1666, though the palco would have been reused in future years. The Falda print dates from 1669, recording the event that year.[6] The print also provides information on the three buildings that sat opposite the Palazzo Venezia on the Piazza di San Marco. This includes the Palazzo Frangipane Vicenzi on the corner of the via San Romualdo and a palace on the site of what would later become Palazzo Bigazzini in 1680, then Palazzo Bolognetti, and ultimately Palazzo Torlonia or Palazzo Bolognetti-Torlonia, after Count Virginio Cenci Bolognetti sold the palazzo to a banker, Alessandro Torlonia between 1803 and 1808.[7] The Palazzo Bolognetti was destroyed in 1903 to open the area for the construction of the national monument for Vittorio Emanuele II and to provide a clear view of the monument from the via del Corso.[8] An additional source that we used for the 3D reconstruction of this palazzo is the Falda print Chiesa Dedicata al Nome di Giesu’ de Padri Giesuiti nel Rione della Pigna (fig. 8), which includes a sliver of one of the palazzi in the background.

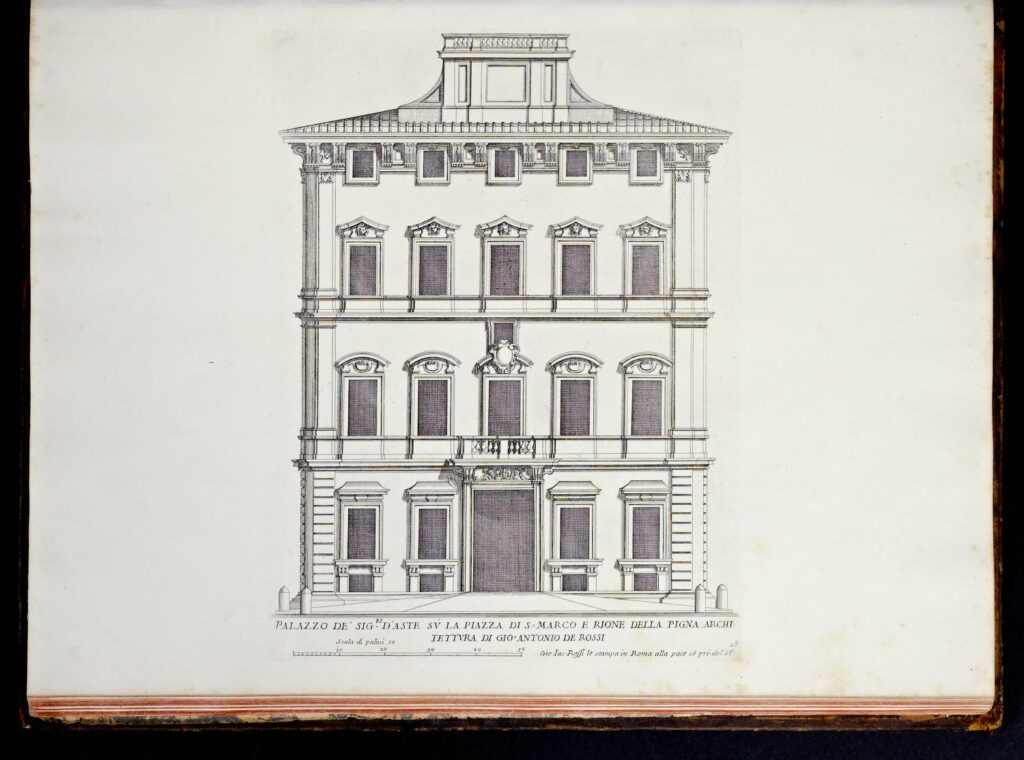

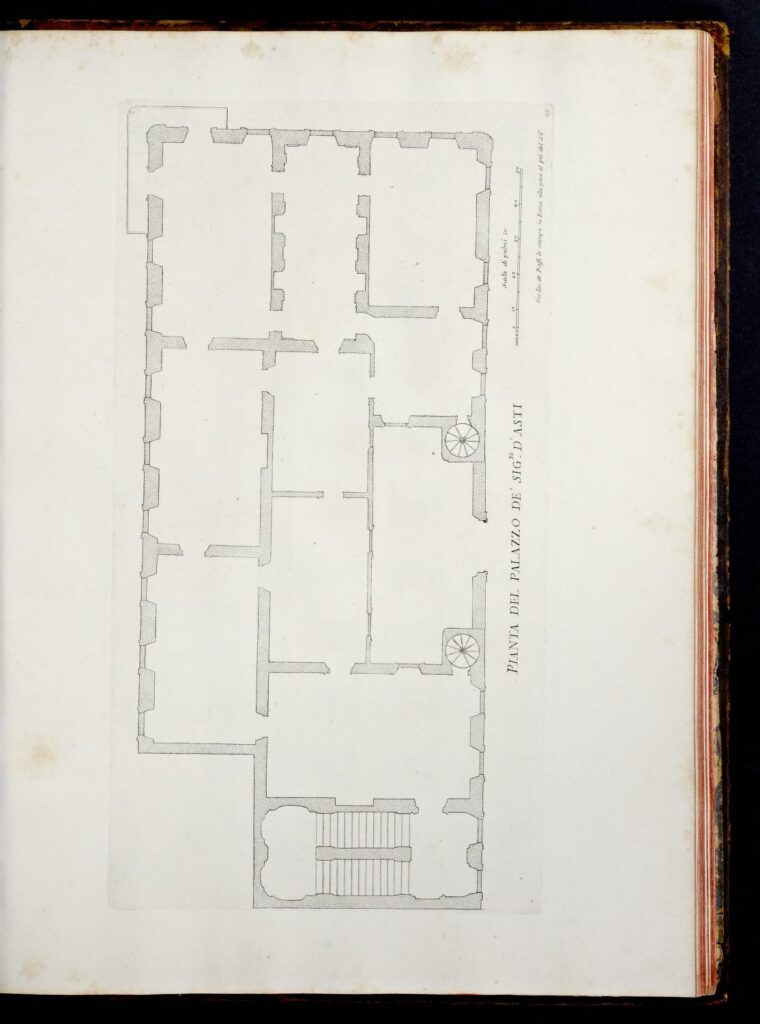

The Palazzo D’Aste, later called the Palazzo D’Aste Rinuccini Bonaparte, occupies a key position at the northwest corner of the Piazza di San Marco and the entrance to the via del Corso. Francesco Bonaventura D’Aste won a bidding competition for the site of this palazzo with a plan that encompassed both the new building and the annexation of his adjacent palazzo. The site became available for purchase through a program begun by Alexander VII in 1657 to regularize the Piazza di San Marco, in this case by ordering the partial demolition of buildings on the corner of the via del Corso and the Piazza in 1658. Construction of the Palazzo D’Aste was largely complete by 1667. D’Aste had agreed to build the sides of the palazzo on the via del Corso and Piazza di San Marco first, so these are likely to have been largely complete by 1665 when Falda depicted them.[9] Though not by Falda, both the façade and plan of this palazzo are featured in Palazzo de’ Sig.ri D’Aste Su La Piazza di S. Marco in Palazzi Di Roma De Piv Celebri Architetti: Nvovi Disegni Dell’Architettvre, E Piante De Palazzi Di Roma De Piv Celebri Architetti (fig. 11 and fig. 12). Falda depicts the side of this palazzo along the via del Corso, identified as the Palazzo de Sig. Hasti, in his Chiesa di Santa Maria in Via Lata Su’ La Via Del’ Corso (fig. 6).

-

Figure 11: Anonymous, Palazzo de’ Sig.ri D’Aste Su La Piazza di S. Marco, c. 1670. -

Figure 12: Anonymous, Pianta Del Palazzo de’ Sig.ri D’Asti, c. 1670.

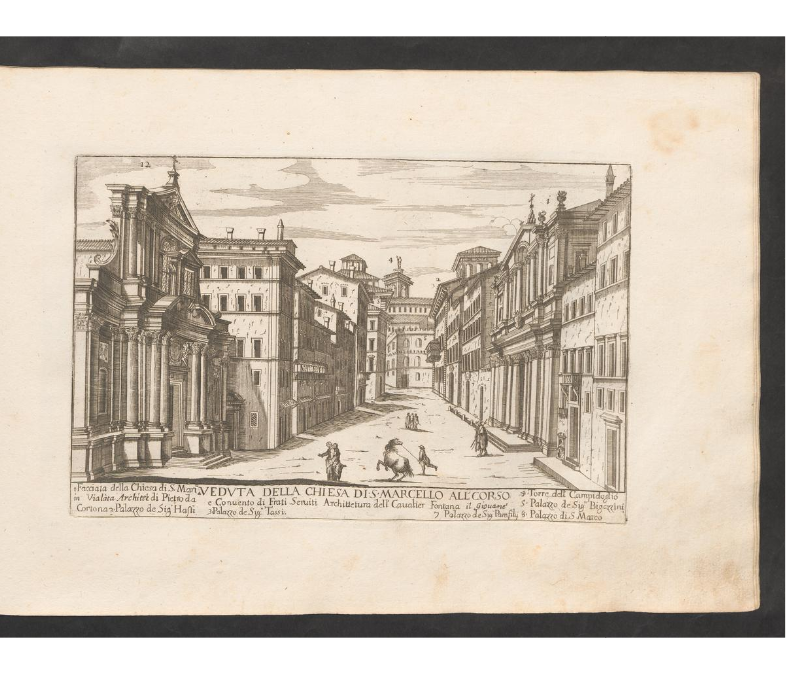

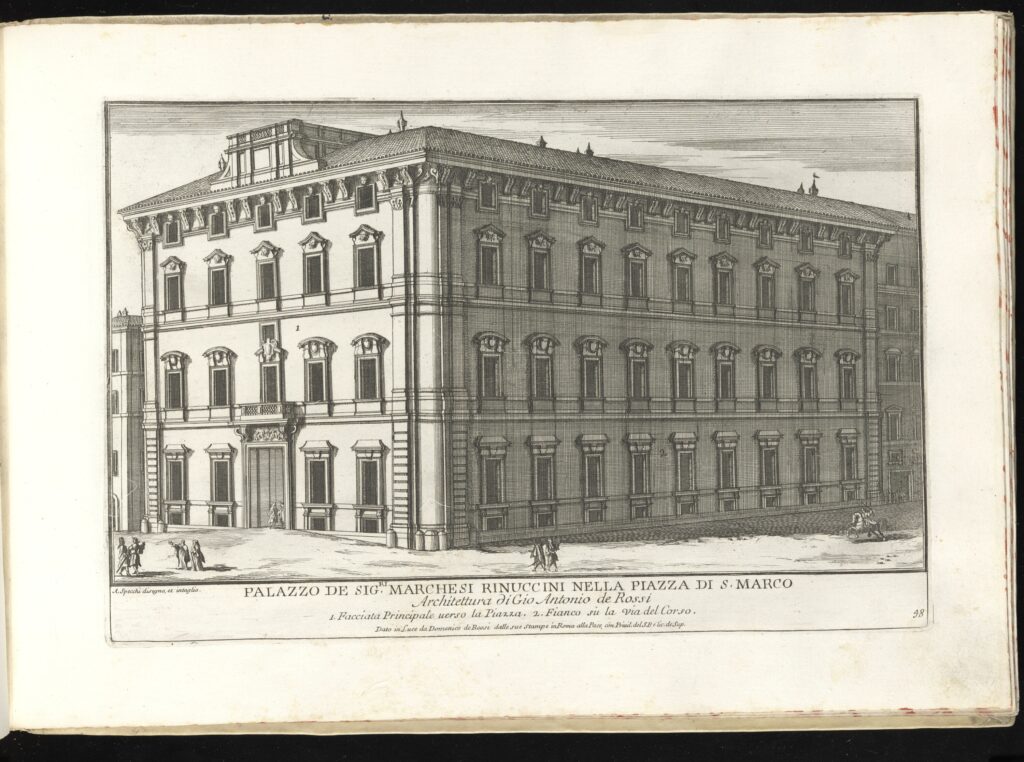

Falda depicts another view of the façade on the Piazza San Marco and the first three bays along the via del Corso in his Strada dalla Piazza di S. Marco alla Chiesa del’ Giesu, where it is also identified as the ‘Palazzo de Sig. Hasti’ (fig. 4). The full via del Corso façade, depicted at an extreme angle from the north, can also be found in a supporting source, Veduta della Chiesa di S. Marcello all’Corso (fig. 13) from Matteo Gregorio De Rossi’s Il nuovo splendore delle fabriche in prospettiva di Roma moderna. The combination of these sources provided good evidence for our reconstruction. The anonymous print from Palazzi, made ca. 1670, (fig. 11) shows the completed palazzo with only minor differences from the façade as it is today.[10] We compared this print with our other sources to decide how to depict the main portal and the top row of windows, which were the two elements that showed differences. Falda’s print from 1663 (fig. 3) lacks a door on the façade facing the Piazza di San Marco, suggesting that the building was not yet complete. Falda’s print Strada dalla Piazza di S. Marco alla Chiesa del’ Giesu (fig. 4) from Il nuovo teatro, published in 1665, shows a similar façade to that in Palazzi, but the central door lacks a balcony over it. While the modern door also lacks a central balcony, the design of the modern portal is quite different from that shown in this print from Il nuovo teatro. In the eighteenth century, Giuseppe Vasi depicted the façade in a way similar to Falda, again without the balcony over the door (fig. 9). However, in Vasi’s view the wall above the central door looks rough, a condition indicated through dots and shading, suggesting the door was either unfinished or was being redesigned. The print by Alessandro Specchi from the end of the seventeenth century depicts the facade as in the Palazzi print (fig. 14). Falda also depicts the top row of windows as square in form in all of his prints. Vasi, a century later, depicts these windows as alternating between square and rectangular, as they do today. As we could not confirm when changes were made to the façade, we followed the specific elements, including the balcony over the main portal, from the Palazzi print (fig. 11), which provides the most detail, and which also matches the details in Specchi’s print. We added the balcony on the corner of the building that is found in all other prints. The Prospetto et Apparato del’ Palco print (fig. 10) from 1666 or later, shows this building’s facade nearly perpendicular to the viewer, it includes a balcony, the position of which, is somewhat ambiguous.

-

Figure 13: M.G. de Rossi, Veduta della Chiesa di S. Marcello all’Corso, 1773. -

Figure 14: A. Specchi, Palazzo De Sig.ri Marchesi Rinuccini Nella Piazza Di S. Marco, 1699.

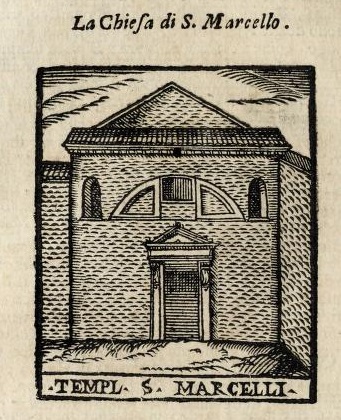

San Marcello al Corso faces the Piazza di San Marcello, just a couple of blocks up the via del Corso from the Piazza di San Marco. The print from Il nuovo splendore, first published in 1686, shows San Marcello al Corso with a complex Baroque façade (fig. 13). An earlier facade is visible in the Pianta di Roma of Tempesta from 1593 that matches the depiction of the façade, shown in greater detail, in an illustration in Roma Antica e Moderna of 1677 (fig. 15).[11] Habel notes that the new façade, while probably ordered in 1662, was not completed at that time.[12] Falda‘s 1676 map (fig. 1) provides a clear view of the facade without its later ornament but with a taller profile than the simple façade shown in Roma Antica e Moderna. Falda’s depiction of 1676 matches that of his earlier 1667 map, Recentis Romae ichnographia et hypsographia sive planta et facies ad magnificentiam qva svb Alexandro VII P.M. vrbs ipsa directa excvlta et decorata est (fig. 16).

-

Figure 15: F. Franzini and V. Mascardi, Roma antica e moderna, 1677. -

Figure 16: G. B. Falda, Recentis Romae ichnographia et hypsographia sive planta et facies ad magnificentiam qva svb Alexandro VII P.M. vrbs ipsa directa excvlta et decorata est, 1667.

Hellmut Hager proposed that the death of Alexander VII may have delayed construction of the new facade. By 1672 a new facade had been at least in part constructed. The cronista del Convento noted at the time that the “struttura della nuova facciata” had blocked light from rooms inside. The precise state of the facade at this point is unknown. Records indicate continued construction into the 1680s.[13] Thus, the state of completion of the new facade in 1676 cannot be confirmed. To best accommodate this, we used Falda’s 1676 map as our primary source for this façade (fig. 1), since it shows the full façade with only some of the new changes taking place. Falda depicts three windows and a shield over the central door (fig. 17).

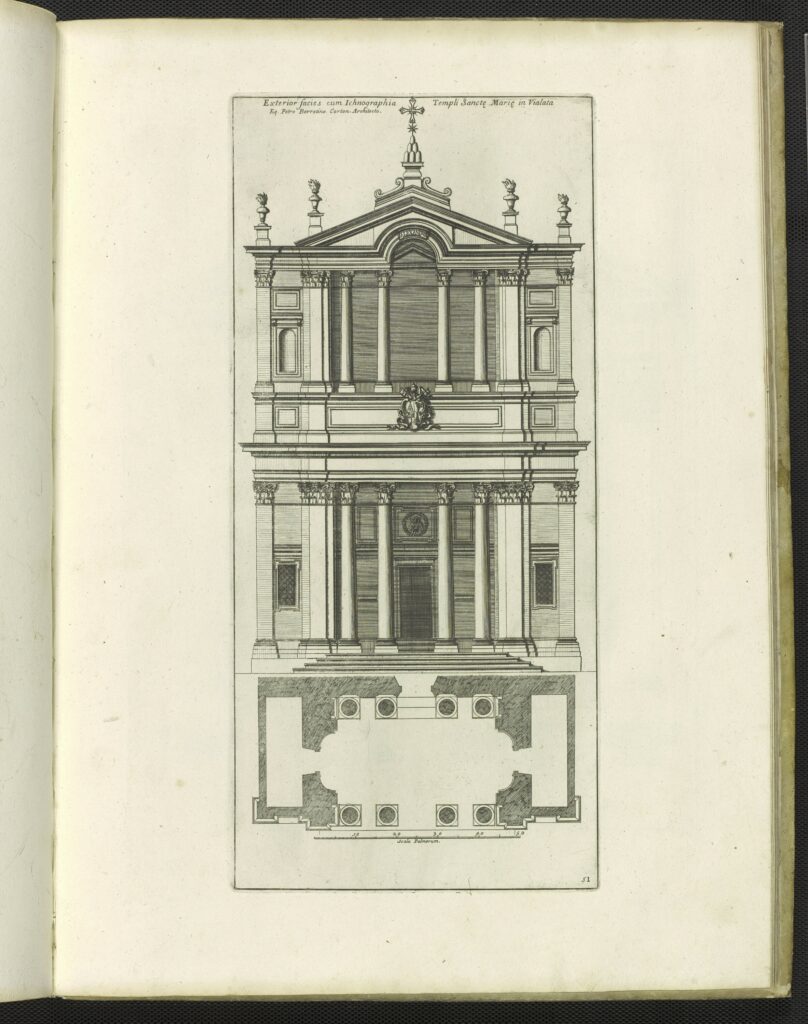

On the opposite side of the via del Corso is the Chiesa di Santa Maria in via Lata, which was founded as early as the 9th century, but went through multiple phases of construction. A major renovation was begun in 1639. The façade, however, recalling a triumphal arch, was not executed until 1662, based on a design by Pietro da Cortona (fig. 18).[14]

Giovanni Battista Falda and Lieven Cruyl both depict this church on the via del Corso in precise views. Falda’s Chiesa di Santa Maria in Via Lata Su’ La Via Del’ Corso (fig. 6) and Cruyl’s Santa Maria in Via Lata (fig. 19) provided the major sources for the 3D reconstruction of this church. A view of Santa Maria in via Lata can also be found in Veduta della Chiesa di S. Marcello all’Corso (fig. 13) from Il nuovo splendore, though this print is slightly later and lacks the refined detail of our other sources. There are minor differences between the bell towers shown in Cruyl and Falda; we chose to follow that of Falda.

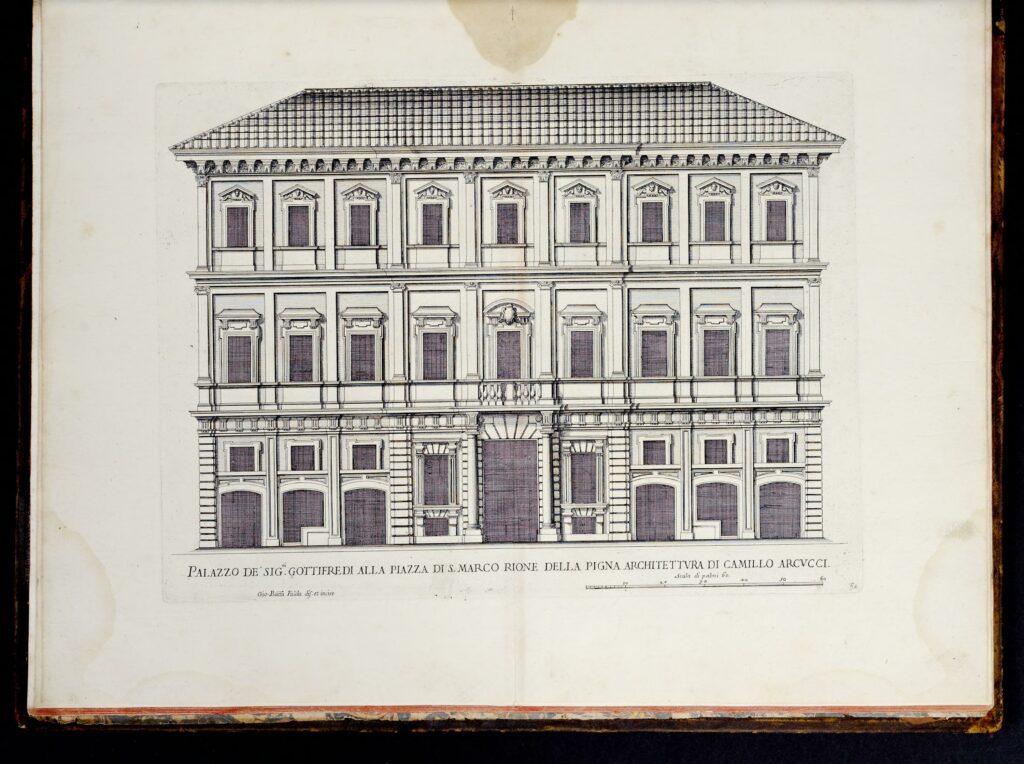

The Palazzo Gottifredi, later called the Palazzo Grazioli, depicted by Falda in Palazzo de’ SS.ri Gottifredi alla Piazza di S. Marco Rione della Pigna architettura di Camillo Arcucci (fig. 20) in Palazzi Di Roma De Piv Celebri Architetti, sits along the modern via del Plebiscito, just west of the Piazza di San Marco. A palazzo in this location was originally constructed according to the design of Giacomo della Porta, but the Gottifredi decided to renovate under architect Camillo Arcucci during the pontificate of Alexander VII, allowing for its inclusion as “new” in the Palazzi volume.[15] A detail of the façade elevation showing the portal, surrounding windows, and architectural decoration appears in a print made around the turn of the eighteenth century by Carlo Quadri and Antonio Barbey (fig. 21), providing further visual information for reconstructing the palazzo.

-

Figure 20: G.B. Falda, Palazzo de’ SS.ri Gottifredi alla Piazza di S. Marco Rione della Pigna architettura di Camillo Arcucci, 1655. -

Figure 21: C. Quadri and A. Barbey, Porta del Palazzo de Sig.ri Gottifredi nella Piazza di S. Marco, 1702.

To digitally reconstruct the area of Rome around the Piazza di San Marco, we used a combination of sources. Falda’s map provided a clear source for the buildings on the eastern side of the street between San Marcello al Corso and the Piazza di San Marco. The western side of the street is not visible on the map, so for the buildings between Santa Maria in via Lata and the Palazzo D’Aste, we compared Falda’s Chiesa di Santa Maria in Via Lata Su’ La Via Del’ Corso (fig. 6) with Cruyl’s Santa Maria in Via Lata print (fig. 19). Finally, for the smaller buildings between the Palazzo D’Aste and the Palazzo Gottifredi opposite the Palazzo Venezia, we looked to the details that Falda depicts in Strada dalla Piazza di S. Marco alla Chiesa del’ Giesu (fig. 4).

The reconstruction of this area now provides a view of the relationship between the via del Corso and the Capitoline hill that has been lost in modern times (fig. 22).

[1] Pietrangeli 1977, 96-102, 106.

[2] Pietrangeli 1977, 102-110.

[3] Barberini 2008; Barberini, Schiavon, and De Angelis d’Ossat 2011, 17, 79-115, Notes on the various changes and restorations to the building from 1654-1758 can be found on pages 176-218.

[4] Blunt notes that the Palazzo Venezia does not have any Baroque features, other than the fountain by Benedict XIII, erected in 1730. Blunt 1982, 199; De Rossi, and Falda c. 1670.

[5] Tice et al. 2008, http://vasi.uoregon.edu/catalog/ entry 039.

[6] McPhee 2024. Personal correspondence from Sarah McPhee, who cites Bjurström 1966, and Magnuso 1982.

[7] McPhee 2024. Personal correspondence from Sarah McPhee. Felisini 2016, 17-49, esp. 35.

[8] Catterson 2017, 211; Tice 2005-2023, https://web.stanford.edu/group/spatialhistory/nolli/ entry 277.

[9] On the history of the D’Aste palace see Habel 1990, 301-307.

[10] Habel 1990, 293-309.

[11] Hager 1973, 58-74.

[12] Habel 1990, 308, f. 75.

[13] Hager 1973, 58-74.

[14] Pietrangeli 1977, 48-56.

[15] Pietrangeli 1980, 72-76.

Figures:

- Figure 1: “Detail of the Piazza di San Marco” from Giovanni Battista Falda. 1676. Nuova pianta et alzata della citta’ di Roma con tutte le strade, piazza et edificii de tempi, palazzi, giardini et altre fabbriche antiche e moderne come si trovano al presente nel pontificato do N.S. Papa Innocentio XI con le loro dichiarationi nomi et indice copiosissimo. Collection of the Rijksmuseum, Object number: RP-P-OB-207.658 (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by the Rijksmuseum, http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.587478).

- Figure 2: “Detail of the Piazza Venezia” from Nolli, Giambattista. 1748. Nuova Pianta di Roma. Roma: s.n. Collection Archive.org (https://archive.org/details/gri_33125008447415/page/n30) (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Archive.org and scanned by Getty Research Institute).

- Figure 3: “Detail of the piazza e stradone a S. Marco” from Giovanni Battista Falda. 1663. Disegno delle fabriche prospettiue e piazze fatte nouamente in Roma d’ordine della sta. di N.S. Papa Alexandro VII. Folger Shakespeare Library Collection. Source Call Number: ART Box R763 no.29 (size L) (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by the Folger Shakespeare Library, CC-BY-SA-4.0).

- Figure 4: Giovanni Battista Falda. 1665. “Strada dalla Piazza di S. Marco alla Chiesa del’ Giesu Diretta et Ampliata da N. S. Papa Alesandro VII” in Il nvovo teatro delle fabriche, et edificii, in prospettiva di Roma moderna, vol. 1, print 16. Collection of Emory University Libraries (artwork in the public domain, photography provided by Emory University Readux https://readux.io/volume/nuovoteatro5vol/page/nuovoteatro5vol_00000035.tif).

- Figure 5: Giovanni Battista Falda. 1643-1678. Piazza di San Marco. Collection of the Nationalmuseum of Stockholm Sweden (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Nationalmuseum CC-PD https://collection.nationalmuseum.se:443/eMP/eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface&module=collection&objectId=158639&viewType=detailView).

- Figure 6: Giovanni Battista Falda. 1665. “Chiesa di Santa Maria in Via Lata Su’ La Via Del’ Corso Fatta da N.S.Papa Alesandro VII” in Il nvovo teatro delle fabriche, et edificii, in prospettiva di Roma moderna, vol. 1, print 17. Collection of Emory University Libraries (artwork in the public domain, photography provided by Emory University Readux https://readux.io/volume/nuovoteatro5vol/page/nuovoteatro5vol_00000037.tif).

- Figure 7: Giovanni Battista Falda. 1669. “Chiesa Dedicata alla Madonna de’ Loreto de Fornari nella Regione de Monti” in Il nvovo teatro delle fabriche, et edificii, in prospettiva di Roma moderna, vol. 3, print 7. Collection of Emory University Libraries (artwork in the public domain, photography provided by Emory University Readux https://readux.io/volume/nuovoteatro5vol/page/nuovoteatro5vol_00000121.tif).

- Figure 8: Giovanni Battista Falda. 1669. “Chiesa Dedicata al Nome di Giesu’ de Padri Giesuiti nel Rione della Pigna” in Il nvovo teatro delle fabriche, et edificii, in prospettiva di Roma moderna, vol. 3, print 20. Collection of Emory University Libraries (artwork in the public domain, photography provided by Emory University Readux https://readux.io/volume/nuovoteatro5vol/page/nuovoteatro5vol_00000147.tif).

- Figure 9: Giuseppe Vasi. 1752. “Piazza S. Marco” in Delle magnificenze di Roma antica e moderna libro secondo, che contiene le piazze principali di Roma con obelischi, colonne, ed altri ornamenti. Dedicate alla sacra real maestà di Maria Amalia Walburga … da Giuseppe Vasi da Corleone … e dal medesimo fedelissimamente disegnate, ed incise in rame, secondo lo stato presente, a’ quali si aggiunge una breve spiegazione di tutte le cose notabili in dette piazze. In Roma. Print 39. Collection of David Rumsey Map Collection, David Rumsey Map Center, Stanford Libraries. (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by David Rumsey Map Collection via Archive.org CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 https://archive.org/details/dr_piazza-s-marco-g-vasi-dis-inc-39-to-accompany-delle-magnificenze-di-13008153).

- Figure 10: Giovanni Battista Falda. c. 1666-1669. “Prospetto et Apparato del’ Palco Dove la Maesta’ della Regina di Svetia ne’ Giorni del’ Carnevale si Trattiene a Vedere il Corso de’ Palii et Comparsa delle Maschere su la Piazza di San Marco in Roma.” Collection of the Rijksmuseum Object Number RP-P-OB-36.032 (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by the Rijksmuseum http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.108969). Date based on personal correspondence with Sarah McPhee (2024).

- Figure 11: Anonymous. c. 1670. “Palazzo de’ Sig.ri D’Aste Su La Piazza di S. Marco e Rione della Pigna Architettura di Gio. Antonio de Rossi” in Palazzi Di Roma De Piv Celebri Architetti: Nvovi Disegni Dell’Architettvre, E Piante De Palazzi Di Roma De Piv Celebri Architetti. Print 28. Collection of the Getty Research Institute (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Archive.org scanned by the Getty Research Institute https://archive.org/details/gri_33125012602732/page/n148/mode/1up).

- Figure 12: Anonymous. c. 1670. “Pianta Del Palazzo de’ Sig.ri D’Asti” in Palazzi Di Roma De Piv Celebri Architetti: Nvovi Disegni Dell’Architettvre, E Piante De Palazzi Di Roma De Piv Celebri Architetti. Print 29. Collection of the Getty Research Institute (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Archive.org scanned by the Getty Research Institute https://archive.org/details/gri_33125012602732/page/n150/mode/1up).

- Figure 13: Matteo Gregorio de Rossi. 1773. “Veduta della Chiesa di S. Marcello all’Corso” in Il nouvo splendore delle fabriche in prospettiva di Roma moderna. In Roma: presso Carlo Losi. Collection of ETH Library, Rar 1314. (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by ETH Library CC0 https://www.e-rara.ch/zut/content/zoom/4111676).

- Figure 14: Alessandro Specchi. 1699. “Palazzo De Sig.ri Marchesi Rinuccini Nella Piazza Di S. Marco” in Il nuovo teatro delle fabriche, et edificii, in prospettiva di Roma moderna. Roma: cura di Gio. Iacomo Rossi. vol. 4, print 48. Collection of Emory University Libraries (artwork in the public domain, photography provided by Emory University Readux https://readux.io/volume/nuovoteatro5vol/page/nuovoteatro5vol_00000277.tif).

- Figure 15: Franzini, Federico, and Vitale Mascardi. 1677. Roma antica e moderna: nella quale si contengono chiese, monasterij, hospedali, compagnie, collegij e seminarij: tempij, teatri, anfiteatri, naumachie, cerchi, fori, curie, palazzi e statue: librarie, musei, pitture, scolture, & i nomi de gli artifici: indice de’ sommi pontefici, imperatori, rè, e duchi: con vna copiosissima tauola, e aggiunta di tutte le cose notabili fatte sino al presente Roma: Per il Mascardi, a spese di Federico Franzini. Roma: Per il Mascardi, a spese di Federico Franzini. Collection of the Getty Research Institute (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Archive.org scanned by the Getty Research Institute https://archive.org/details/romaanticaemoder00fran_1/page/140/mode/2up).

- Figure 16: Giovanni Battista Falda. 1667. Recentis Romae ichnographia et hypsographia sive planta et facies ad magnificentiam qva svb Alexandro VII P.M. vrbs ipsa directa excvlta et decorata est. Roma. Collection of Emory University Libraries (artwork in the public domain, photography provided by Emory University Readux https://readux.io/volume/thgrb/page/thgrb_00000001.tif).

- Figure 17: Screenshot of San Marcello al Corso from Envisioning Baroque Rome. The shield above the door and some details have not been added yet.(artwork copyright Sarah McPhee, photograph provided by Envisioning Baroque Rome).

- Figure 18: De Rossi, Giovanni Giacomo. 1684. Insignium Romæ templorum prospectus exteriores interioresque: a celebrioribus architectis inventi: nunc tandem suis cum plantis ac mensuris. Rome: Josephus Jacobo de Rubeis. Collection of Emory University Libraries (artwork in the public domain, photography provided by Emory University Readux https://readux.io/volume/th936/page/th936_00000106.tif).

- Figure 19: Lievin Cruyl. 1665. “Santa Maria in Via Lata.” in Eighteen Views of Rome. Collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art. Dudley P. Allen Fund 1943.263 (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by The Cleveland Museum of Art CC-0 https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1943.263, flipped by author).

- Figure 20: Giovanni Battista Falda. 1655. “Palazzo de’ SS.ri Gottifredi alla Piazza di S. Marco Rione della Pigna architettura di Camillo Arcucci” in Palazzi Di Roma De Piv Celebri Architetti: Nvovi Disegni Dell’Architettvre, E Piante De Palazzi Di Roma De Piv Celebri Architetti. Print 51. Collection of the Getty Research Institute (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Archive.org scanned by the Getty Research Institute https://archive.org/details/gri_33125012602732/page/n194/mode/1up).

- Figure 21: Carlo Quadri and Antonio Barbey. 1702. “Porta del Palazzo de Sig.ri Gottifredi nella Piazza di S. Marco” in Stvdio d’architettvra civile sopra gli ornamenti di porte e finestre tratti da alcune fabbriche insigni di Roma con le misure, piante, modini, e profili : opera de’ piv celebri architetti de nostri tempi Vol. 1. Roma: De Rossi. print 124. Collection of the Getty Research Institute (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Archive.org scanned by the Getty Research Institute https://archive.org/details/gri_33125011212012/page/n252/mode/1up).

- Figure 22: Screenshot of the Piazza di San Marco from Envisioning Baroque Rome. (artwork copyright Sarah McPhee, photograph provided by Envisioning Baroque Rome).

Bibliography

- Barberini, Maria Giulia Museo di Palazzo Venezia. 2008. Tracce di pietra : la collezione dei marmi di Palazzo Venezia. Roma: Campisano.

- Barberini, Maria Giulia, Alessandra Schiavon, and Matilde De Angelis d’Ossat. 2011. La storia del Palazzo di Venezia : dalle collezioni Barbo e Grimani a sede dell’ambasciata veneta e austriaca, Roma : Il Palazzo di Venezia e le sue collezioni di scultura. Roma.

- Blunt, Anthony. 1982. Guide to baroque Rome Accessed from https://nla.gov.au/nla.cat-vn1797143. New York: Granada.

- Bjurström, Per. 1966. Feast and Theatoer in Queen Christina’s Rome. Stockholm.

- Catterson, L. 2017. Dealing Art on Both Sides of the Atlantic, 1860-1940: Brill.

- De Rossi, Giovanni Giacomo and Giovanni Battista Falda. c. 1670. Palazzi di Roma de più celebri architetti. [Roma]: Giovanni Giacomo De Rossi.

- Felisini, Daniela. 2016. Origins and Rise of the Torlonia Family and Bank. In Alessandro Torlonia: The Pope’s Banker, edited by Daniela Felisini. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Habel, Dorothy Metzger. 1990. “Alexander VII and the Private Builder: Two Case Studies in the Development of Via del Corso in Rome.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 49 (3):293-309.

- Hager, Hellmut. 1973. ” La facciata di S. Marcello al Corso. Contributo alla storia della construzione.” Commentari: rivista di critica e storia dell’arte XXIV, 58-74.

- Magnuso, Torgil. 1982. Rome in the age of Bernini. New Jersey: Humanities Press.

- Pietrangeli, Carlo. 1977. Rione IX – Pigna Parte 3, Guide Rionali di Roma. Roma: Fratelli Palombi Editori.

- Pietrangeli, Carlo. 1980. Rione IX – Pigna Parte 1, Guide Rionali di Roma. Roma: Fratelli Palombi Editori.

- Tice, Jim. 2005-2023, (Accessed May 5). “The Interactive Nolli Map Website. https://web.stanford.edu/group/spatialhistory/nolli/.

- Tice, Jim, Erik Steiner, Allan Ceen, and Dennis Beyer. 2008, (Accessed Imago Urbis: Giuseppe Vasi’s Grand Tour of Rome. http://vasi.uoregon.edu/.

Leave a Reply